I knew it was a mistake when I did it. I found a four-pack of tall boys from a B.C. brewery (whom I won’t name) selling for a couple of bucks under the average price at Sherbrooke. It was on the “new release” shelf, meaning it hadn’t been in Alberta long (plus I trust the gang at Sherbrooke to move product quickly and rotate when needed). There was no date stamp or code on the cans. I knew what I was dealing with. I was dealing with a beer that was being dumped into Alberta. I bought it anyway, just to check.

Why do I think they were dumping it? In addition to its suspiciously low price, it was a beer clearly past its prime. The beer gushed upon opening and it had that distinct musty cardboard note of oxidation. The beer was thin and lacked the malt character I expect from the style (I am refraining from indicating the style to prevent identification of the brewery). I also know this is a brewery that doesn’t normally import to Alberta and has a decidedly local focus overall. A strange way to introduce your brand to Alberta.

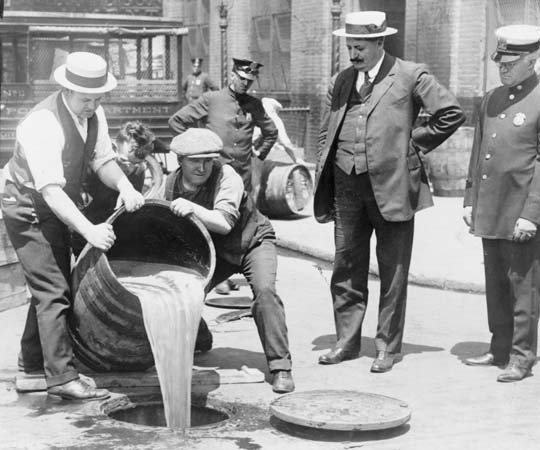

For those of you unaware of the term dumping (in beer terms), it is the practice of taking a nearly expired beer, or a beer that you know you won’t be able to sell in your local market, shipping it to another market, and selling at a reduced price in an effort to recoup some of the costs (even if you lose a bit of money per purchase). It was a major problem in Alberta in the 2000s and early 2010s. And I had hoped it had gone away.

The issue is this. When Alberta privatized liquor retail in the early 1990s, they also unilaterally opened Alberta’s borders to inter-provincial trade. They eliminated the liquor control board’s tasting panel and import restriction rules – which most provinces still retain to this very day – and flung the doors open. To sell a beer in Alberta all you needed was to have registered agent, fill out a two-page form and pay $50. Do that and you were in.

In the early 2000s, Alberta’s craft beer scene lagged behind many provinces, including B.C., Ontario and Quebec. We had, maybe, a dozen breweries struggling to get noticed, even though beer consumers’ tastes were starting to shift. Retail privatization and dumb rules like the minimum production capacity were severely limiting the ability of the industry to grow.

But with open borders, breweries in more vigorous jurisdictions like B.C. and Ontario (and the U.S.) had an opportunity. Given the lack of Alberta-based production, they could easily capture some of that nascent craft beer demand. In many cases, breweries shifted their business model to make Alberta a core component of their target audience and sent fresh beer sold at regular prices to fill the gap. This is perfectly legitimate. However, many breweries realized Alberta was also a great dumping ground. If they overproduced, they could ship the excess to Alberta at discounted prices to move it quickly. They might not make as much money, but it beat tossing beer down the drain.

Some breweries adopted this strategy with fresh beer, intentionally ramping up production higher than they might normally, knowing they had a convenient off-ramp if it didn’t move. Others, more cynically, shipped nearly stale-dated beer to Alberta with the hope that Alberta consumers would be blinded by the reduced price and wouldn’t notice the reduced quality.

It became such a problem that local Alberta brewers started to cry foul. They started lobbying the Alberta government to stem the flow of cheap, often sub-standard imports, which were squeezing them out of shelf space and tap lines. The former Conservative government was mostly deaf to their pleas (although Redford did make some key policy shifts to assist the industry). In 2015 the new NDP government was more receptive. They changed the mark-up policies to advantage locally produced beer over import beer by creating higher mark-ups for imports.

It would be an understatement to say that the policy was controversial. It failed both constitutional and internal free trade challenges and went through a couple of iterations over four years.

But it worked.

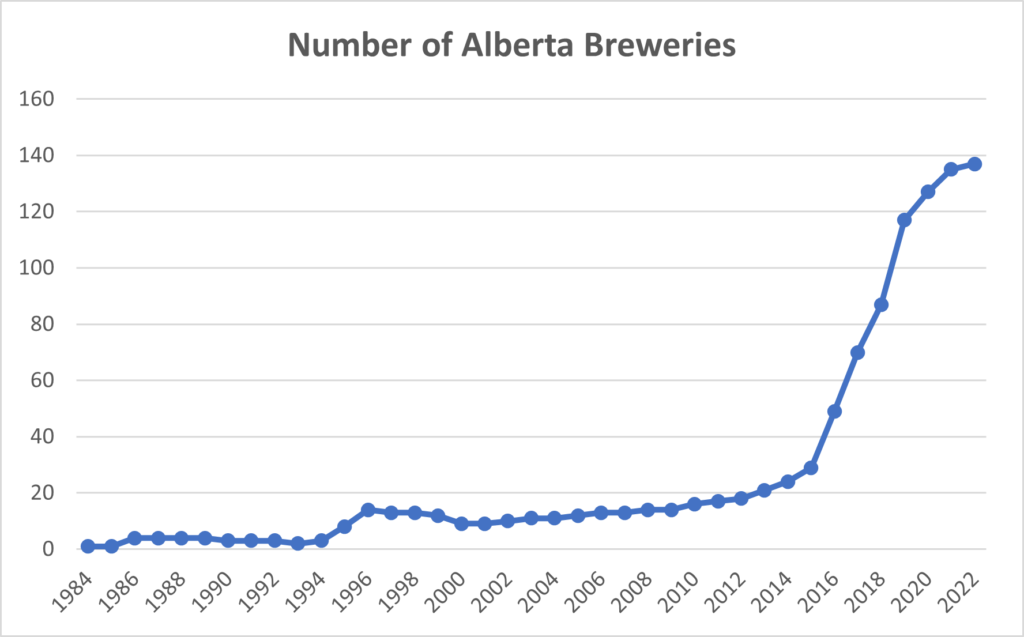

Over the four years the mark-up differential existed, Alberta’s beer scene exploded. By 2019 there were over 100 breweries. I estimate Alberta’s share of the market increased by more than 50%. Alberta breweries had pushed out import beer from tap lines and store shelves. Consumers were embracing Alberta beer.

I am well aware that the mark-up policy is not the only factor leading to Alberta’s beer explosion. The removal of the minimum production capacity was key to encouraging new breweries. Plus there was a growing interest in local food around that time that naturally spilled over into beer. We also can’t dismiss the availability of capital due to the oil downturn, especially in Calgary. But the mark-ups helped breweries elbow their way onto the shelves.

In 2019, the UCP returned to a mark-up policy that treated all beer the same, regardless of origin (they kept graduation by production volume). But by that time Alberta producers had the toehold they needed to stay competitive in the market. Imported beer remains a key segment of the craft beer market in Alberta, but less dominant than it was a decade ago. The province remains the most open market in the country.

Today, Alberta is a very crowded, competitive market. Good beer will sell, but no longer can a brewery trust that just because it is on the shelves it will move. Consumers have far more choice and will naturally gravitate to product that excels in quality, branding and accessibility. To my mind, that would mean dumping no longer works as a strategy. Consumers will no longer buy your product because it is cheap and it is all there is.

But I am thinking I might be wrong. Maybe the ease in which you can enter the Alberta market still makes it tempting for some breweries to use the province as a quick-fix for excess production problems? I cannot see how it is a sustainable strategy, but possibly they hope they can get away with it in the short term. I am not sure why they would want to risk their reputation in this way, but that is their call, I guess.

It is a “free” market and all that, so I appreciate the rule is “buyer beware”. So let this be a public service announcement to consumers to eye new entrants, especially those with discounted prices, with a dose of skepticism. Check the date codes (if possible). Ask yourself if they can make money at that price point. And mostly, let your taste buds guide you. You will know a dumped beer when you taste it.

March 25, 2023 at 1:09 AM

Seeing a couple of beers that showed up on shelves this week it saddened me to see this article as well to prove it is true.

One beer was made back in December and is no longer available. When I saw this beer I asked about it as well when it first came out and I got the “I’m sorry it isnt coming to Alberta at all” answer. only to find that near April it is here.

The second beer from the same brewery was released back in October… and it is a kettle sour… again.. not available in the brewery and you cant find it in most shelves in BC…

This is from a brewery that is TRYING to make a comeback into the market and they are doing a poor job of this by dumping old products onto our shelves!

March 26, 2023 at 4:23 AM

HI..I would like to have a conversation face to face…..and ill buy the beer… Text 780.441.5760 or email gord@integritysystemsinc.com

March 29, 2023 at 8:41 AM

Shame on the store for helping the brewer/agent with this nefarious action!!

March 29, 2023 at 11:30 AM

Hi Sid,

The store may not be aware. In the case I cite it is a store that has a solid reputation for ensuring product is in the best shape possible. Plus if it is wholesaled at a discount, it can be hard for a store to pass up that opportunity. But, true, many retail stores can be quite unscrupulous about product quality.

Thanks for commenting.

March 29, 2023 at 11:38 AM

Thanks goes to Mirella over at Beerology for linking to this story over on her Facebook page.

I’ve been out of the beer scene for a while, and totally forgot about your blog; I apologise.

Hope to see you at our EBGA cask ale festival this coming August. Yes, we’re back!!!

March 29, 2023 at 11:11 AM

I don’t know if I agree with all of this. It’s pretty speculative.

And retail controls import, and as we all know retail in Alberta is privatized.

So it’s retail’s ultimate responsibility to make sure that what is sold is good quality. And they will ask for credit from producers if it is bad quality.

Also…

as a producer i was invited to supply beer to Alberta. It was a holiday release that I had to produce and ship in early August. Can you even imagine? It was approaching stale-datedness when it went to the shelves for sale in mid December.

The article makes no mention of this.

March 29, 2023 at 11:28 AM

Thanks for your insights, Henry.

Liquor distribution is complex, so I full acknowledge there are multiple factors at play, including delays along the supply line. I imagine shipping from Nova Scotia poses a number of challenges regarding timing.

But this is more than speculative. I have spoken to many people in the industry who confirm this practice exists. And we can see consistent patterns with some breweries (closer than Nova Scotia) who list stale beer sold at reduced rates. I don’t name them as my focus is on public policy failings rather than to “gotcha” breweries.

Also, I don’t agree that all the responsibility falls on the retailer. They don’t see stale dates when they order from the warehouse – and the example I cited didn’t provide any kind of dates. Plus it is the producer (or their agent) that sets the wholesale price. It is the brewery’s decision to deeply discount a product. There are multiple pieces at play.

Finally, in my opinion those holiday “advent” packs, which I suspect it was in your case, are highly problematic due to the long lag time. The special packaging requires the beer to be made FAR too early. In my opinion consumers – and producers – should be leery of those projects.

Thanks for commenting. Onbeer always appreciates healthy, respectful discussion.

April 12, 2023 at 11:26 AM

We have the same problem in Saskatchewan. The bee leaves BC fresh, but by the time it goes through “the system” and sits on liquor store shelves, it isn’t. Then it goes “on sale” and when you bring it home and open one, it explodes.

April 12, 2023 at 11:27 AM

beer