I get a lot of questions from craft beer consumers in Alberta about the future of the industry in the province. Many fear that the market is “saturated” – especially in Calgary – and worry we will see a fallback. Others wonder if the next big step is just around the corner. And then, of course, there is the impact of COVID-19.

It is too soon to make final conclusions on COVID’s effect as we are just now getting back to normal operations (and let’s hope it stays that way). How consumer preferences have shifted is still not fully known. Plus I anticipate additional brewery closures in the coming months as cash reserves dry up and bridge loans come due. I will do a full analysis of COVID in a few months once the dust has settled.

For now, let’s take a broader look at the state of Alberta’s beer industry and where it is going. There are things we know and things we can only speculate. Let’s start with what we know.

1. The Boom

Alberta has long lagged behind provinces such as Ontario, B.C., and Quebec in terms of provincial-based production and craft beer culture. There were many reasons for that, which I have discussed many times (including here and here). That all changed in the past few years.

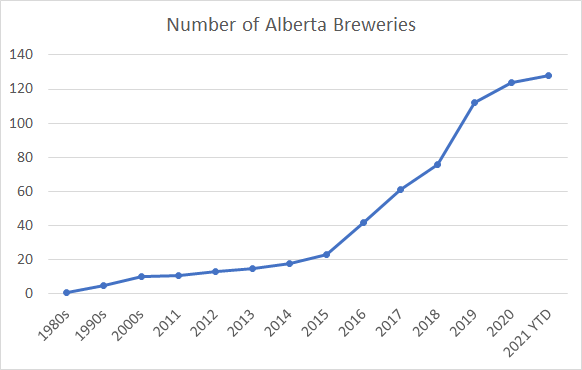

The five-year period between 2015 and 2019 was a craft beer boom by any definition. There were 18 brewing licenses in Alberta in 2014 (I am using a different definition than I use in my per capita posts). By the end of 2019 there were 118. In five years 102 new breweries opened up (there were a few closures as well). That is a remarkable number. The chart below tracks the number of brewing licenses in Alberta over time. It would look even more impressive if I hadn’t collapsed the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s into three data points. (Source for all charts: author’s personal database of Canadian breweries.)

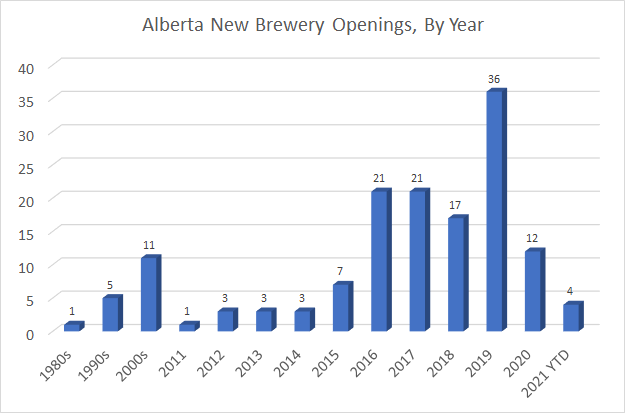

Another related way to examine the boom is to examine the number of new breweries that open each year. The chart below does this. It does not subtract for brewery closures, so the numbers between the charts will not align. Again keep in mind that blip in the 2000s really tells us there was only an average of one new brewery a year. The years 2016 to 2019 were the most active for openings.

It is this dizzying growth that caused a stir. Consumers (and beer writers) couldn’t keep up. As early as 2016 I was hearing voices saying the pace of growth was unsustainable. Yet it kept going until last year. I will come back to the question of sustainability.

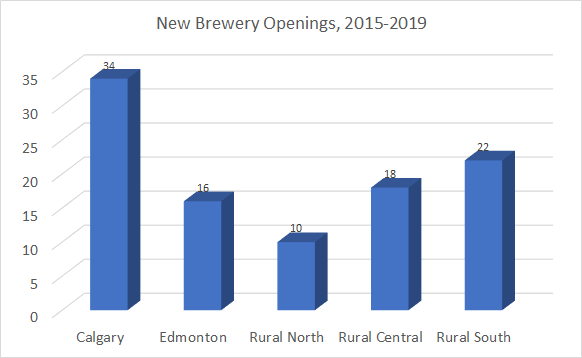

The other factor to consider is the geographic diversity of the growth, shown in the chart below. Aside from Calgary, the distribution of new breweries was fairly even across the regions (when considering the north’s sparse population base). Distribution WITHIN the regions is also quite even, as breweries popped up in every small city and town. This suggests the boom was a province-wide phenomenon not just confined to the two major cities. (And, yes, I know Lethbridge, Medicine Hat, Red Deer and so on are not “rural”.) The data also explains why much of the sustainability worries came out of Calgary.

As a quick aside, the data makes a strong case that the policies and political environment during the Notley government had an impact on the growth of the industry. I recognize these kinds of things are complex and can never be reduced to a single policy or event. We can’t forget the groundwork laid by the removal of the minimum production capacity rule and also must pay attention that momentum creates more momentum. That said, there was clearly a trend of new breweries under the Notley regime. Given most breweries take 18 to 36 months to go from conception to production (this is a rough average, the standard deviation is huge), it does mean most were creatures of the 2015-2019 policy regime.

But I digress. The clear conclusion here is that Alberta experienced a beer production boom unseen anywhere in this country (other provinces have seen more a slow burn over a longer period).

2. Post-Boom

The above charts reveal a leveling off of the growth over the last eighteen months or so. 2021 is on track to see the fewest number of new breweries since before the boom. This data is much harder to interpret and we will really only know what is going on in a couple of years. But let’s try anyway.

First, we can’t ignore COVID. One thing we do know is that the pandemic delayed breweries’ openings. Every one of the new breweries opening during this period report significant COVID-related delays in procuring tradespeole, getting permits, and receiving equipment. This fact only takes us so far, however.

Even in late 2019 and early 2020 before the pandemic took hold industry observers were noting fewer breweries under construction and less talk of new projects. And given timelines for building a brewery most breweries who slated a 2020 or early 2021 opening would have been too far along to abort completely (space secured, equipment ordered, etc.).

That said it is likely that COVID may have caused projects in earlier stages to either hit pause or full stop. The economic conditions aren’t great for any new public-facing business right now. The unknown is how many of those paused projects will start up again in the coming months.

It is more plausible to interpret recent trends as the boom in new breweries coming to an end. As mentioned the pace of new projects had already slowed. The most recent Alberta Craft Beer Guides list in their “Soon-eries and Rumour-ies” sections 11 projects with definite bricks-and-mortar plans (not counting contract brewers). Compare that to the Winter 2017 edition which listed 33 projects (not all opened).

New breweries will continue to open, but the pace has slowed. The number of new breweries this year and likely next will be more than the dry 2000s but not be close to the peaks of the last few years. The boom is over.

3. What Next?

Where does that leave the Alberta industry? That’s the hard part. But let me give it a shot.

First I want to dispel any notion that the industry is “saturated”. It is not. Precise figures are hard to find, but Alberta-made craft beer makes up approximately 10% to 12% of all beer sold in the province, and a good chunk of that is Big Rock’s production (at about 5%). For comparison, Ontario is closing in on 20% and B.C. is over 20%. There is plenty of room for growth. The pandemic demonstrated consumers continue to seek out local options.

Second, was the growth between 2015 and 2019 sustainable? Had that kind of torrid pace continued for five more years, maybe not. But the low number of closures – eight – of breweries opening during that period suggest the pace was sustainable at that time. And keep in mind COVID took down a couple of those operations.

The recent slowdown is both expected and a natural market correction. As fewer and fewer “open spaces” exist in the market (be that geographically or stylistically) fewer entrepreneurs are going to risk their money on a new brewery. COVID may have accelerated that shift, but it was already beginning to happen.

I argue Alberta is entering a maturation phase in its development. Fewer new entrants and existing breweries consolidate their existing market and look for ways to expand production or distribution (or not, depending on the business model). Growth in market share will come from current breweries slowly tapping into new consumers.

We will likely see a bump in closures over the next couple years, only some due to COVID (although it will be hard to disentangle the factors). This, too, is not unexpected and a sign of a maturing industry. If every brewery that opens succeeds it is a sign of an imbalance between supply and demand. As that gap narrows, consumers will be more discerning and breweries with inadequate cash flow, poor marketing and branding, and/or poor quality will be left behind.

The final factor to consider is that beer, as a market segment, is in decline. Craft beer continues to grow but beer overall is losing share to wine, cider, hard seltzers and ready-to-drink product. Sustainability in Alberta’s craft beer industry will be determined by its ability to gain greater share of the existing pie. In my opinion, breweries producing their own craft versions of hard seltzer and the like only play at the margins of what is a much bigger issue.

What comes after the boom? For Alberta beer likely a quieter, steady-path growth as the industry matures, the players evolve and it becomes a mainstay for Alberta beer consumers. One thing is for sure, Alberta breweries should not be banking on another boom anytime soon and should shift their strategies to ensure longer term survival. Actually, that is likely sound advice for all Albertans.

Leave a Reply