In my latest Planet S column this week, I take a look at the role yeast plays in beer’s flavour and aroma. You can read the whole article here, but be aware the article is aimed at the average beer consumer (at least those who are interested enough to read my columns). More experienced beer geeks, and in particular homebrewers, know full well the sizeable impact yeast has.

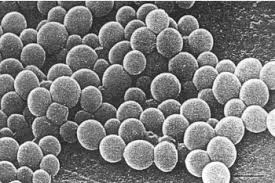

I believe even the most ardent beer aficionados too often overlook the impact of yeast. We get all caught up in hop varieties, grain bills, hopping regimes and the other ingredients in beer. This is understandable; we can see and touch all of those things. Yeast, on the other hand, is invisible. It is the quiet, silent workhorse of the beer world. Which means it is often under-appreciated for its contribution (like many reliable, loyal and uncomplaining workhorses in the world). Its non-observable nature is what led pre-Pasteur brewers to call the magic of fermentation “God is Goode”.

The reality is the fundamental division of beer – ale vs. lager – is almost entirely due to the two species of yeast used for beer fermentation. Lager yeast and ale yeast prefer different conditions (cool vs. warm) and produce vastly different profiles. The reason lagers are cleaner, smoother and crisper is, in part, due to the qualities of the yeast (also due to the period of cold aging post-fermentation). Ale yeasts produce more fruity esters and give the impression of more body.

We all know the famous cases of yeast strains affecting flavour – Belgian, Weizen and Wit yeasts are all prime candidates. Their effect is pronounced and thus not easily ignored. But two things are often ignored. First even the choice of which example of a Belgian yeast to use can fundamentally alter the phenolic compounds that make up the patented peppery, funky Belgian ale flavours.

Second, even so-called pedestrian strains, the large collection of British, German and American yeasts whose impacts are less pronounced, can alter a beer far more than we imagine. I remember a few years ago gearing up to brew my oatmeal stout (a recipe of which I am particularly fond). I religiously use an Irish Ale strain that I believe accents the malty base of the beer without compromising the roast finish. However that particular batch, for reasons that now escape me (likely a woeful lack of advance planning on my part), that strain was not available. I went with a popular American Ale strain, one known for its clean profile and hop enhancement.

Big mistake.

The resulting beer lacked the fullness of body and the hefty malt tones that are essential backbone to a good stout. As a result the roast finish was too sharp, as the beer lacked appropriate balance. Maybe had I designed an American Stout, with a more pronounced bitterness and less emphasis on maltiness, the yeast would have worked out fine. However, not with what I wanted. Painful lesson learned (okay, not that painful. I drank the beer anyway as there was nothing particularly wrong with it).

There is a reason many breweries carefully select their “house yeast”. They know it will create a signature flavour profile that can be found in all their beer. Of course, choosing to use just one yeast is also a practical solution to deal with yeast management – small breweries don’t have the resources to juggle too many yeasts. But brewers know yeast leaves its mark and they want people to consistently recognize their beer as THEIR beer.

Yeast is under-appreciated. One need not have a degree in micro-biology to value the role they play. So the next time you have a pint, pause for a moment and say thank you to the yeast that worked so hard to make that beer for your. A simple “God is Goode” would suffice.

May 22, 2014 at 6:51 PM

I have experimented (who, me?) with using Belgian and lambic blend yeasts in Imperial IPAs. Despite substantial hopping (often in the 90-100 IBU range), the yeast really affects the perception of bitterness, and they do not come across as very bitter at all, especially compared to almost identical beers brewed with American Ale yeasts.

May 23, 2014 at 10:29 AM

Interesting experiences, Ernie. I always find bitter Belgian beer interesting (and not always in a good way). Occasionally a brewery finds the right mix, but Belgian yeast spice and hops are not necessarily met to be together. It takes a particular hop strain and a recognition that you can’t make a hop bomb in that style.